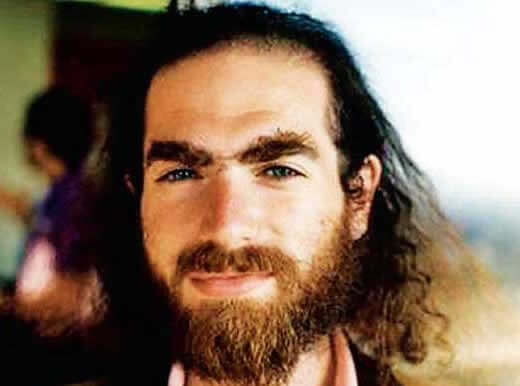

Grigori Perelman (ISTJ)

I should probably lead into this article by stating that we are aware most people will probably disagree with this. However, after reading Perfect Rigor and some online sources, we think that Grigori Perelman probably falls more in line with an Si-Te, rather than an Ni-Te. (We saw plenty of evidence for Te/Fi, which ruled out all other types.) We are also aware that it has been suggested that he has Aspergers, which obviously makes his personality much more complicated, and could account for certain anomalies. Although, I will note that Grigori Perelman is already much more complicated from a research perspective due to the limited firsthand information about him.

Note: Grigori Perelman is also called “Grisha”, so when you see that name in the quotes, it’s referring to him.

Si:

“I was working on different things, though occasionally I would think about the Ricci flow. You didn’t have to be a great mathematician to see that this would be useful for geometrization. I felt I didn’t know very much. I kept asking questions.”

“One should never force oneself on anyone”

“In retrospect, one might suppose that topology ultimately attracted him as the quintessence of mathematics– the province of pure categories and clear systems, with no informational interference–but as a first year student, he was barely exposed to topology.” – Author of Perfect Rigor

“There are a lot of students of high ability who speak before thinking. Grisha was different. He thought deeply. His answers were always correct. He always checked very, very carefully. He was not fast. Speed means nothing. Math doesn’t depend on speed. It is about deep.” – Yuri Burago

As a child, Perelman appeared to follow the rules strictly, with no regard to nuance of circumstance. When his mother told him to never untie his hat or else he’d catch a cold, he wouldn’t even untie it in the heated subway car. One of his instructors noted this as unusual, since typically one would at least untie the ear pieces. He was a good student, and never spoke up in class unless he felt the need to correct something. He didn’t get distracted, and focused on the problem at hand. Later in his teen years, while PE was his worst class, he followed all instructions without complaint. As a general rule, it was noted that Perelman would always follow the rules and instructions without protestation (when the instructor was in a position of authority), no matter how ridiculous the exercises seemed to be.

Perelman was very systematic in his approach to things, like in the way he approached vocal music. However, he deemed castrati to be unnatural. Perelman learned precision with his words as he aged. However, he tended to struggle with cutting down information to what was most important. He would tell the story of how he solved the problem every time. This suggested Si, rather than Ni. Perelman was also known for never making mistakes, even honest ones, due to his incredible precision. He was slow and calculated. When he published his proof, Perelman disliked anyone claiming that he solved it, partly because he didn’t yet view it as perfected or complete.

Perelman wore the same clothes everyday. He basically ate the same food as well, and even went out of his way in the US to get the bread and milk that he was accustomed to. Some people claimed that he rejected cars as unnatural, which sounds more in line with an unhealthy Si trait, not wanting to accept something he wasn’t accustomed to. It was also noted that he was still angry thirty years later about being forced to quit the violin in order to focus on math. Later in life, he would accept invitations to take part in mathematical community events, especially for children. It was suggested that he did this out of respect for the traditions of clubs and competitions that he had been raised in, and not because he liked kids.

Overall, he was known for being reclusive, quiet, modest and reserved, which, of course, point generally to being an introvert. He avoided social events, unless they were specifically for other mathematicians.

Te:

“Well, whether a problem is interesting depends on whether there’s any chance of solving it.”

“If they know my work, they don’t need my C.V.,” he said. “If they need my C.V., they don’t know my work.”

“He had now tasted the blood of a freshly killed competitor, and his ambitions far exceeded his accomplishments.” – Sergei Rukshin

Perelman was generally unemotional, and tended to lack empathy. When taken to summer camp to instruct around the age of 16, Perelman turned out to be rigid, hypercritical and demanding. He gave his students problems way higher than their capability, with little regard for their abilities. He also tried to enforce strict punishments, which got overruled by his superiors. As a whole, Perelman struggled to recognize perspectives that differed from his own. The way he saw it was the way it was. He was blunt with others, and didn’t care for social niceties. During graduation, he didn’t thank the school like all of the other graduates. His papers and writing also tended to be terse and to the point.

As a student, Perelman would only ever speak up in class to correct an error, which can easily be seen as Te driven. He was also hyper strict with himself, even far into adulthood. He had very well known standards of behavior, and when those were not met, he would enforce them. Some of these seemed a bit extreme, like viewing sloppy footnotes as plagiarism. I’ll talk more about his standard in the Fi section. This all generally pointed to the more controlling and rigid nature of Te. As a child, he was encouraged to read more, but argued against it since anything that was necessary would be in the school’s required reading. He also refused to participate in extracurricular activities that were nonintellectual and noncompetitive.

Perelman was arrogant and competitive. (Competition would speak to the results-driven nature of Te.) He found it unacceptable to receive a second place prize, and worked ceaselessly to ensure that it never happened again (Si). During a competition in his teen years, Perelman felt the need to shout and physically grab one judge by the tail of his suit jacket because they tried to leave before they had listened to the other possible solutions he had devised. This physical need to stop them and force them to listen, even though he’d won, suggests Te. (This example is also mentioned in the Ne section, but for a different reason, since it’s an example of both Te and Ne working in combination.)

Fi:

“I didn’t worry too much myself. This was a famous problem. Some people needed time to get accustomed to the fact that this is no longer a conjecture. I personally decided for myself that it was right for me to stay away from verification and not to participate in all these meetings. It is important for me that I don’t influence this process.”

“I’m a disciple of Hamiton’s, though I haven’t received his authorization.”

“He has moral principles to which he holds. And this surprises people. They often say that he acts strange because he acts honest, in a nonconformist manner, which is unpopular in this community–even though it should be the norm. His main peculiarity is that he acts decently. He follows ideals that are tacitly accepted in science.” – Mikhail Gromov

Perelman held very strict standards and appeared to verbalize them. He believed in following rules, and didn’t approve when others broke them. He refused to help others cheat. He found lying to be unacceptable and hated people who did it. He believed that a certain style of footnotes was plagiarism, and berated others for it, even though it was a common practice and not deemed unacceptable by others in the community. Perelman also made sure not to take any money that he didn’t believe himself owed. When he found out that the university had been overpaying him with leftover grant money (a common practice), he found out the exact amount and forced the university to take it back (Si-Te-Fi). He was prone to being dismayed by the lax ethics of others.

Perelman had no problem discussing his work with other mathematicians, but he hated journalists. He also hated anyone implying that he had completed the proof for profit, or that he’d claimed to have solved it. He refused awards (both monetary and honorary). In reference to refusing the one million dollar prize, Perelman told Interfax, “to put it short, the main reason is my disagreement with the organized mathematical community. I don’t like their decisions, I consider them unjust.”

Perelam made his work available online for free, and prevented it from getting officially published for any kind of gain. Perelman was generally disappointed in the world of mathematicians for attempting to make merchandise of his work, especially before it was perfected and no one understood it fully.

Ne:

“If everyone is honest, it is natural to share ideas.”

Perelman’s inferior Ne comes out in a few different ways. Firstly, during school, he was never interested in experiences and field trips, which suggests a low extraverted perceiving function. He also delayed picking a specific focus or specialization, which was unusual for students there. He attended every lecture and seminar he could, which spanned across disciplines, even ones not required, as if trying to universally educate himself in mathematics. This is indicative of Si/Ne, possibly wanting to weed through his options before picking or gain a broad base of knowledge. He also liked working on several problems at once, and him deeming cars to be unnatural could have been a fear of new things.

Lastly, during one of his early competitions, he was explaining his solution to one of the problems to the judges. Two of them turned to leave, saying that it was correct. He yelled “Wait! There are three more possible outcomes.” Having multiple potential outcomes to a problem, in a competition scenario when there should only be one, suggests Ne. As mentioned earlier, the physical need to proclaim and enforce this would be Te.

External Sources:

- Perfect Rigor: A Genius and the Mathematical Breakthrough of the Century

- Manifold Destiny

- Russian mathematician rejects $1 million prize

- A mad, principled genius

- How Grigori Perelman solved one of Maths greatest mystery

Hi there! If you enjoyed that article, leave us a quick comment to encourage us to keep writing, and check out our Updates and Current Projects. In addition, if you've found our content helpful, please consider Buying Us A Coffee to help keep this website running. Thank you!

Hi Great article! I have noticed that there is a common stereotype that most academicians or professors or research professionel are either INTJs or INTPs. Having worked with numerous people from academia last few years I can say with certainly that it’s clearly not so. Most of the academically brilliant people I currently know now and I can recall have been predominantly STJs and NFPs. Funnily enough there are very very few Ti users in this space, especially STPs. Maybe it’s because academia as a system is pretty interdependent and laden with Te protocol rules and credentials which Ti users kind of find it overwhelming and controlling to the autonomy they seek. Any thoughts on this?

Thank you! And inttereesttinggg! That seems plausible. I don’t have much personal experience in this area, coming from the tech/IT world (where I see a lot of Ti and Ne). Logically speaking, it never made sense to me that certain careers would be exclusive to certain types, since people’s interests aren’t dictated by their type alone. Although, I recognize that certain careers might appeal more predominantly to certain types over others, generally speaking, creating a majority of certain types within certain fields.

In my personal life, I’ve met the stereotypical INTPs that enjoy lecturing and teaching, although they haven’t specifically been in academia. I knew an ESFJ who was a molecular biologist (or something of that nature) who turned teacher later. STPs specifically tend to want to do something that’s more immediately applicable to the physical world somehow, so I can see why they might be scarce in that arena. (The STPs I know in real life have been IT, psychology, military, operating room technician, business…) Personally, I would think that SJs would make excellent researchers. It does bug me that it’s assumed that academia is the realm of the INTPs and INTJs, especially since it plays a huge role in people mistyping as one of those two.